Advanced Packaging Becomes a New Battlefield

U.S. President Joe Biden has adopted a two-pronged approach to curb China's high-tech progress, limiting China's access to cutting-edge chips while supporting U.S. semiconductor production. He will further ratchet up the pressure by shifting focus to an emerging area of competition for technological supremacy: semiconductor packaging processes increasingly seen as a path to higher performance.

Metrans is verified distributor by manufacture and have more than 30000 kinds of electronic components in stock, we guarantee that we are sale only New and Original!

Only the United States has recognized the potential of so-called advanced packaging: China is also taking advantage of sanctions-free areas to capture global market share and has made unprecedented progress in manufacturing high-end chips.

Technology analyst Jim McGregor, founder of Tirias Research, said: "Packaging is the new pillar of innovation in the semiconductor industry, and it will revolutionize the entire industry." For China, which does not yet have the most advanced capabilities, "it will definitely be easier for them to improve here." , because it is not subject to U.S. government restrictions. "Encapsulation can help them bridge the gap," he said.

Until recently, the business of semiconductor packaging — encapsulating chips in materials that both protect them and connect them to the electronic devices they belong to — was at best an afterthought in the industry. So it was outsourced, mostly to Asia, with China the main beneficiary: Today, the U.S. has just 3% of the world's packaging capacity, according to Intel Corp.

Yet suddenly, advanced packaging is everywhere: Intel sees it as a core part of the U.S. chip giant's strategy to regain competitiveness; China sees it as a means of building domestic semiconductor capacity; and now Washington is embracing it as part of its self-sufficiency plan a part of.

More than a year after the CHIP and Science Act was introduced, the Biden administration has outlined plans for a $3 billion National Advanced Packaging Manufacturing Initiative following the recent appointment of the center's director. U.S. Department of Commerce Deputy Secretary Laurie Locascio said the goal is to establish multiple high-volume packaging facilities by the end of the century and reduce reliance on Asian supply lines, which constitute an "unacceptable" problem for the United States. Security Risk.

A White House official said the president "has made it a priority to ensure U.S. leadership in all elements of semiconductor manufacturing, with advanced packaging being one of the most exciting and critical areas."

With advanced packaging quickly becoming a new front in the global chip conflict, some believe it's long overdue.

So far, the administration has focused on subsidies to bring chip manufacturing back to the United States, but "we can't ignore packaging because you can't have one without the other," said Rep. Jay Oberolte, R-Calif. said he is one of two vice presidents and chairs the Congressional Artificial Intelligence Caucus. “If packaging is still done overseas, it doesn’t matter if 100% of our chip manufacturing is done domestically,” he added.

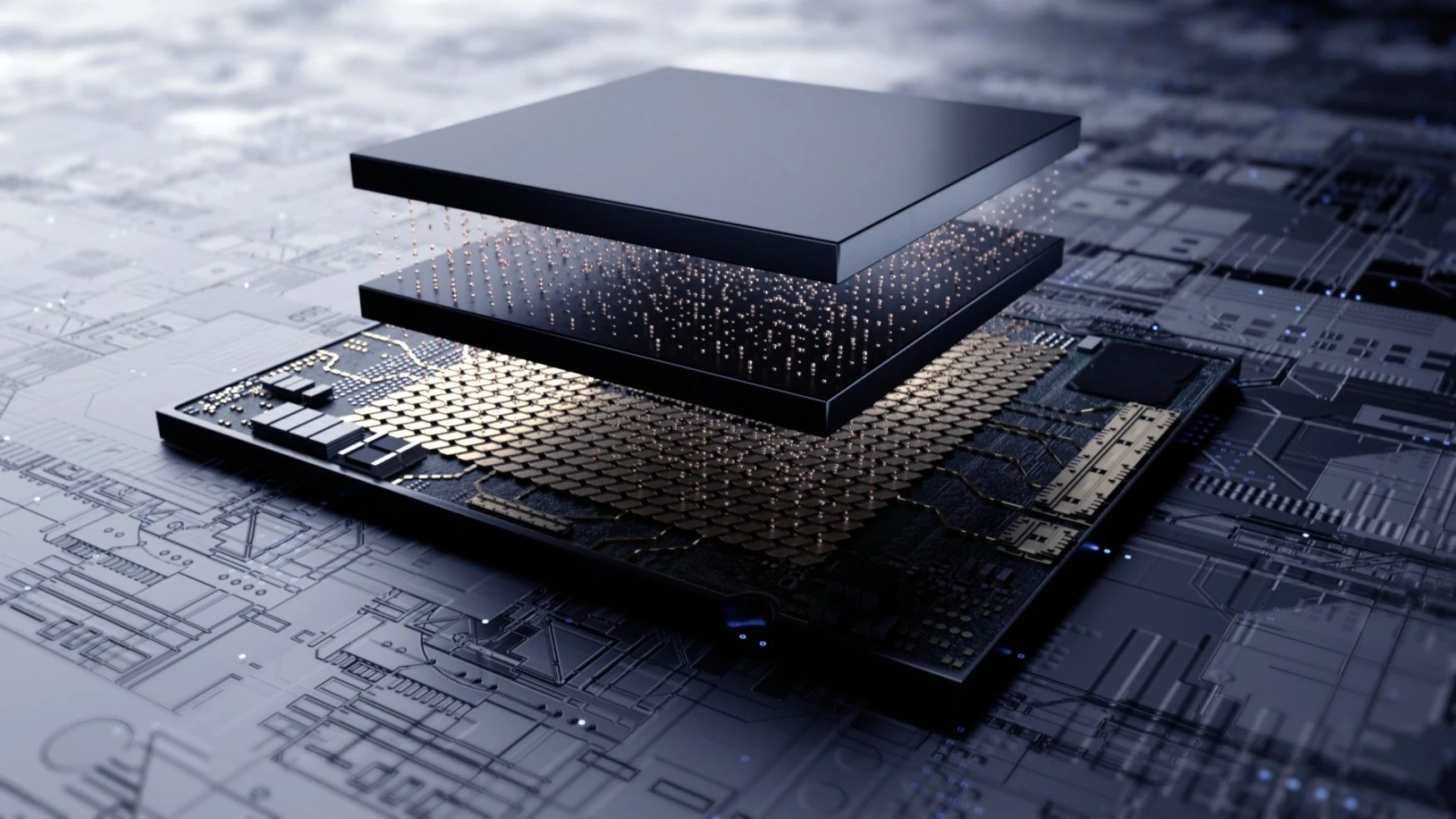

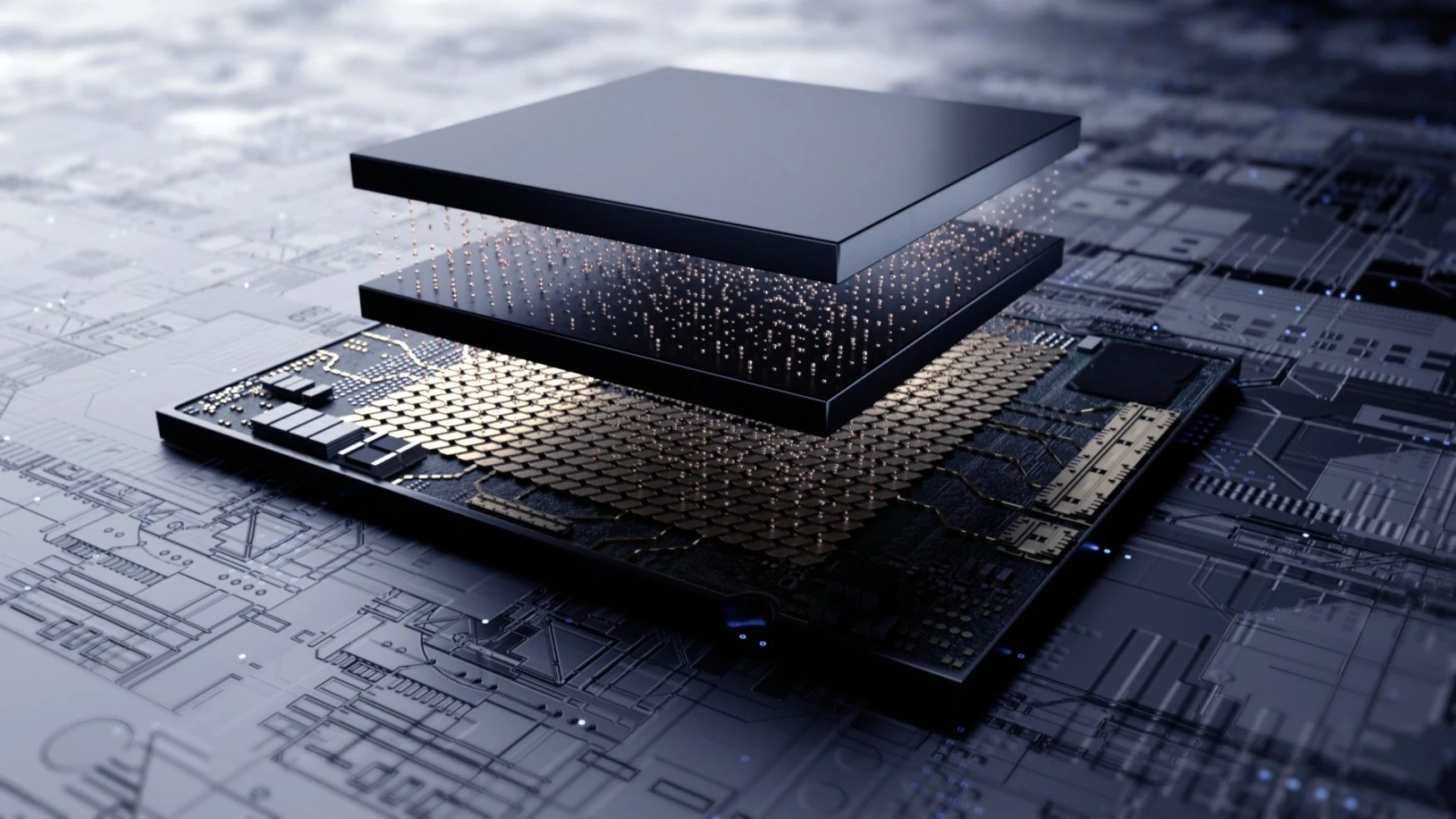

Assembly, test, and packaging—often considered together as “back-end” manufacturing—have always been the most obscure end of the semiconductor industry, innovating compared to the “front-end” business of making chips with functions measured in them. Less and lower added value. However, the complexity of chips is increasing rapidly as new technologies enable them to be combined, stacked and enhance their performance, leading industry executives to call it an inflection point.

Advanced packaging won't help China compete with America's leading semiconductor development, but it could allow Beijing to build faster and cheaper computing systems by splicing disparate chips tightly together. In this case, China could keep its latest chip technology (which is expensive and likely to be limited in quantity) for the most important parts of the chip, and use older, cheaper technology to implement shortcomings in experience management. and sensor control and other functional chips are integrated into a powerful package.

It's a "critical solution," said Charles Shum, a technology analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. "It not only increases chip processing speed, but crucially enables seamless integration of various chip types." The result, he said, "will reshape the semiconductor manufacturing landscape."

China has long regarded semiconductor packaging technology as a strategic priority. China ranks first in the world with a 38% share of the global assembly, test and packaging market, according to U.S. data. While it lags behind Taiwan and the United States in advanced technology, analysts agree that unlike wafer processing, it is in a better position to catch up.

China's Betty already owns the largest number of back-end facilities, including Changdian Technology Group, the world's third-largest packaging and test company, whose revenue is behind Taiwan's ASE Group and U.S.-based Amkor Technology. In addition, Chinese companies are expanding their market share, including Changdian Technology's acquisition of an advanced factory in Singapore and the construction of an advanced packaging factory in its hometown of Jiangyin.

One reason for the sudden focus on this particular technology is its necessity for high-power semiconductors needed for artificial intelligence applications. In fact, a shortage of a specific type of packaging called chip-on-wafer-on-substrate (CoWoS) is a key bottleneck in Nvidia's AI chip production.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Nvidia's main chipmaker, pledged this summer to invest $3 billion in packaging plants to help ease lockdowns. CEO CC Wei told investors on the company's third-quarter earnings call that the company plans to double its CoWoS capacity by the end of next year.

Jun He, vice president of advanced packaging technology at TSMC, said at a conference in Taipei in October that although TSMC has been researching this technology for 12 years, it is only a niche application that only started to emerge this year. “We are building capacity like crazy,” Jun He said, adding that “everyone, maybe even Starbucks,” is talking about CoWoS.

It's not just TSMC. Micron is building a $2.75 billion back-end factory in India, while Intel has agreed to build a $4.6 billion assembly and test plant in Poland and invest about $7 billion in advanced packaging in Malaysia. South Korea's SK Hynix said last year that it planned to invest US$15 billion to build a packaging plant in the United States.

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger said in an interview that "we have some very unique technologies in the packaging space right now." “Everyone working on AI chips today says, wow, this is how I improve the capabilities of my AI chips.”

Some analysts predict this will bring huge fortunes to companies in the space. McKinsey said high-performance chips for data centers, artificial intelligence accelerators and consumer electronics will create the greatest demand for advanced packaging technologies.

Jeffries analysts Mark Lipacis and Vedvati Shrotre wrote in a report on September 14 that chip shipments using advanced packaging are expected to increase 10 times in the next 18 months, but if it becomes standard in smartphones , this number may soar to 100 times. The technology is part of a "tectonic shift" in the industry.

The reason Raimondo mentioned is that chip manufacturing is approaching the limits of physics.

Over the past fifty years, chip performance has continued to improve, thanks in large part to advances in production technology. These components now contain up to tens of billions of tiny transistors, allowing them to store or process information. But now the path to progress, known as Moore's Law after Intel's founder, is facing fundamental obstacles that make improvements more difficult and costly.

Moore's Law (more of an observation) states that the number of transistors on a chip will double approximately every two years. As progress slows, with companies "unable to deliver twice as many transistors every two years at half the cost, twice the clock speeds and lower power levels, the industry has begun to rely more on advanced packaging" technologies to pick up the slack. ," Lipasis and Shlott wrote.

Instead of cramming smaller and smaller components onto a single piece of silicon, many designers and companies are touting the benefits of a modular approach, building products with multiple "chips" tightly packed into the same package.

That explains why Dutch specialist chip packaging tool maker BE Semiconductor Industries NV's value has doubled in the past 12 months to about $9.8 billion, more than double the Philadelphia Semiconductor Index.

That still pales in comparison to the amounts associated with front-end manufacturing — Dutch company ASML NV, which has a near-monopoly on the machines needed to produce cutting-edge semiconductors, is worth nearly $250 billion. Intel's cutting-edge chip manufacturing plant in the eastern German city of Magdeburg will cost $30 billion, more than four times its commitment in Malaysia.

However, between the new Magdeburg plant in Ireland and its Polish plant with advanced packaging capabilities, "Poland may actually be the most important," Kissinger said.

Metrans is verified distributor by manufacture and have more than 30000 kinds of electronic components in stock, we guarantee that we are sale only New and Original!

Only the United States has recognized the potential of so-called advanced packaging: China is also taking advantage of sanctions-free areas to capture global market share and has made unprecedented progress in manufacturing high-end chips.

Technology analyst Jim McGregor, founder of Tirias Research, said: "Packaging is the new pillar of innovation in the semiconductor industry, and it will revolutionize the entire industry." For China, which does not yet have the most advanced capabilities, "it will definitely be easier for them to improve here." , because it is not subject to U.S. government restrictions. "Encapsulation can help them bridge the gap," he said.

Until recently, the business of semiconductor packaging — encapsulating chips in materials that both protect them and connect them to the electronic devices they belong to — was at best an afterthought in the industry. So it was outsourced, mostly to Asia, with China the main beneficiary: Today, the U.S. has just 3% of the world's packaging capacity, according to Intel Corp.

Yet suddenly, advanced packaging is everywhere: Intel sees it as a core part of the U.S. chip giant's strategy to regain competitiveness; China sees it as a means of building domestic semiconductor capacity; and now Washington is embracing it as part of its self-sufficiency plan a part of.

More than a year after the CHIP and Science Act was introduced, the Biden administration has outlined plans for a $3 billion National Advanced Packaging Manufacturing Initiative following the recent appointment of the center's director. U.S. Department of Commerce Deputy Secretary Laurie Locascio said the goal is to establish multiple high-volume packaging facilities by the end of the century and reduce reliance on Asian supply lines, which constitute an "unacceptable" problem for the United States. Security Risk.

A White House official said the president "has made it a priority to ensure U.S. leadership in all elements of semiconductor manufacturing, with advanced packaging being one of the most exciting and critical areas."

With advanced packaging quickly becoming a new front in the global chip conflict, some believe it's long overdue.

So far, the administration has focused on subsidies to bring chip manufacturing back to the United States, but "we can't ignore packaging because you can't have one without the other," said Rep. Jay Oberolte, R-Calif. said he is one of two vice presidents and chairs the Congressional Artificial Intelligence Caucus. “If packaging is still done overseas, it doesn’t matter if 100% of our chip manufacturing is done domestically,” he added.

Assembly, test, and packaging—often considered together as “back-end” manufacturing—have always been the most obscure end of the semiconductor industry, innovating compared to the “front-end” business of making chips with functions measured in them. Less and lower added value. However, the complexity of chips is increasing rapidly as new technologies enable them to be combined, stacked and enhance their performance, leading industry executives to call it an inflection point.

Advanced packaging won't help China compete with America's leading semiconductor development, but it could allow Beijing to build faster and cheaper computing systems by splicing disparate chips tightly together. In this case, China could keep its latest chip technology (which is expensive and likely to be limited in quantity) for the most important parts of the chip, and use older, cheaper technology to implement shortcomings in experience management. and sensor control and other functional chips are integrated into a powerful package.

It's a "critical solution," said Charles Shum, a technology analyst at Bloomberg Intelligence. "It not only increases chip processing speed, but crucially enables seamless integration of various chip types." The result, he said, "will reshape the semiconductor manufacturing landscape."

China has long regarded semiconductor packaging technology as a strategic priority. China ranks first in the world with a 38% share of the global assembly, test and packaging market, according to U.S. data. While it lags behind Taiwan and the United States in advanced technology, analysts agree that unlike wafer processing, it is in a better position to catch up.

China's Betty already owns the largest number of back-end facilities, including Changdian Technology Group, the world's third-largest packaging and test company, whose revenue is behind Taiwan's ASE Group and U.S.-based Amkor Technology. In addition, Chinese companies are expanding their market share, including Changdian Technology's acquisition of an advanced factory in Singapore and the construction of an advanced packaging factory in its hometown of Jiangyin.

"For China, advanced packaging would be a good bet because so far it's been a safe space where everyone has invested," said Mathieu of Taiwan's Institute Montaigne think tank, which studies the geopolitics of technology. Mathieu Duchatel said.

One reason for the sudden focus on this particular technology is its necessity for high-power semiconductors needed for artificial intelligence applications. In fact, a shortage of a specific type of packaging called chip-on-wafer-on-substrate (CoWoS) is a key bottleneck in Nvidia's AI chip production.

Taiwan Semiconductor Manufacturing Co., Nvidia's main chipmaker, pledged this summer to invest $3 billion in packaging plants to help ease lockdowns. CEO CC Wei told investors on the company's third-quarter earnings call that the company plans to double its CoWoS capacity by the end of next year.

Jun He, vice president of advanced packaging technology at TSMC, said at a conference in Taipei in October that although TSMC has been researching this technology for 12 years, it is only a niche application that only started to emerge this year. “We are building capacity like crazy,” Jun He said, adding that “everyone, maybe even Starbucks,” is talking about CoWoS.

It's not just TSMC. Micron is building a $2.75 billion back-end factory in India, while Intel has agreed to build a $4.6 billion assembly and test plant in Poland and invest about $7 billion in advanced packaging in Malaysia. South Korea's SK Hynix said last year that it planned to invest US$15 billion to build a packaging plant in the United States.

Intel CEO Pat Gelsinger said in an interview that "we have some very unique technologies in the packaging space right now." “Everyone working on AI chips today says, wow, this is how I improve the capabilities of my AI chips.”

Some analysts predict this will bring huge fortunes to companies in the space. McKinsey said high-performance chips for data centers, artificial intelligence accelerators and consumer electronics will create the greatest demand for advanced packaging technologies.

Jeffries analysts Mark Lipacis and Vedvati Shrotre wrote in a report on September 14 that chip shipments using advanced packaging are expected to increase 10 times in the next 18 months, but if it becomes standard in smartphones , this number may soar to 100 times. The technology is part of a "tectonic shift" in the industry.

The reason Raimondo mentioned is that chip manufacturing is approaching the limits of physics.

Over the past fifty years, chip performance has continued to improve, thanks in large part to advances in production technology. These components now contain up to tens of billions of tiny transistors, allowing them to store or process information. But now the path to progress, known as Moore's Law after Intel's founder, is facing fundamental obstacles that make improvements more difficult and costly.

Moore's Law (more of an observation) states that the number of transistors on a chip will double approximately every two years. As progress slows, with companies "unable to deliver twice as many transistors every two years at half the cost, twice the clock speeds and lower power levels, the industry has begun to rely more on advanced packaging" technologies to pick up the slack. ," Lipasis and Shlott wrote.

Instead of cramming smaller and smaller components onto a single piece of silicon, many designers and companies are touting the benefits of a modular approach, building products with multiple "chips" tightly packed into the same package.

That explains why Dutch specialist chip packaging tool maker BE Semiconductor Industries NV's value has doubled in the past 12 months to about $9.8 billion, more than double the Philadelphia Semiconductor Index.

That still pales in comparison to the amounts associated with front-end manufacturing — Dutch company ASML NV, which has a near-monopoly on the machines needed to produce cutting-edge semiconductors, is worth nearly $250 billion. Intel's cutting-edge chip manufacturing plant in the eastern German city of Magdeburg will cost $30 billion, more than four times its commitment in Malaysia.

However, between the new Magdeburg plant in Ireland and its Polish plant with advanced packaging capabilities, "Poland may actually be the most important," Kissinger said.